Ubiquitous Object Invisible Object

By Adrian Fernandez

︎ (the text)

︎ (the archive)

In this current situation of extreme isolation, access to the essentials of life have become increasingly limited.

In their place, alternatives, often virtual, have proliferated, designed to replicate and simulate these essentials. One such example is Google Arts and Culture, the omniscient search provider’s Street View-style virtualisation of museums and other cultural institutions.

It is meant to make the world’s treasures more accessible to all. In pursuing that goal, it has also inadvertently created windows into the strange interstitial space between our real and online worlds.

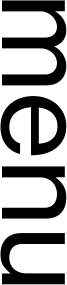

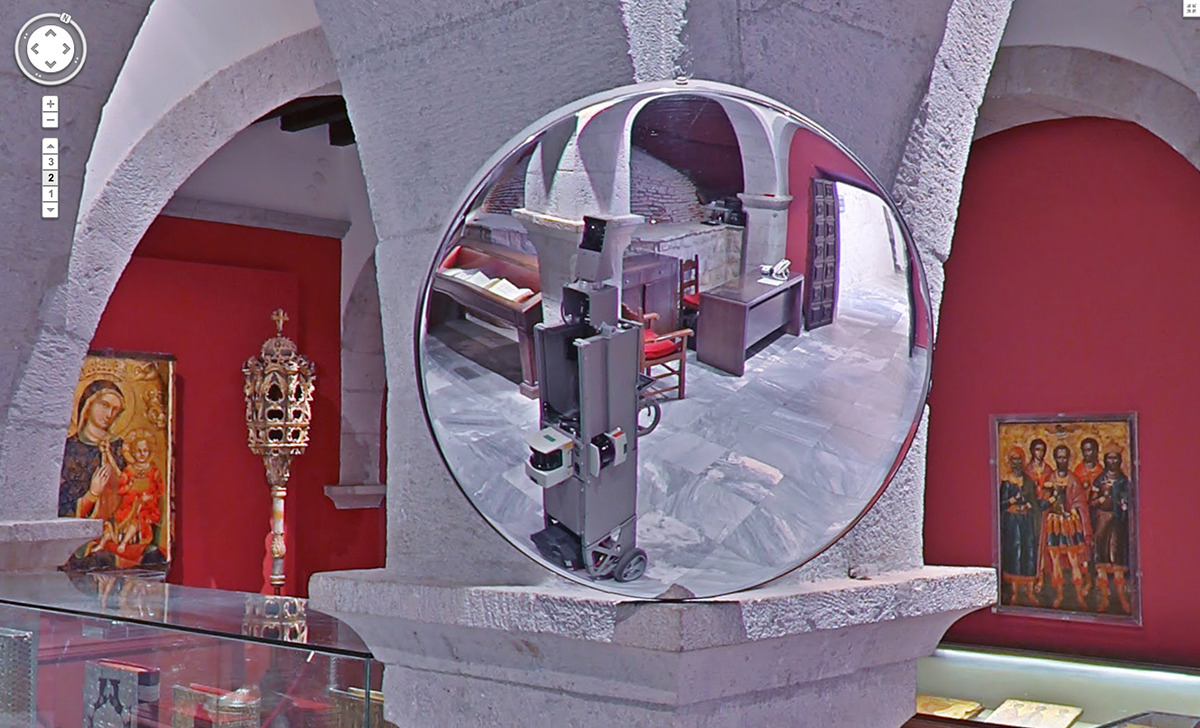

Wander past a mirror, and the sense of roaming a museum is suddenly shattered as you find yourself staring into the compound-eye of the machine behind the illusion.

Looking like Hal-9000 in high heels, the robot looking back holds the camera Google uses to capture the images it stitches together to recreate the museum, our unblinking vessel through the virtual world.

It embodies questions about the complex meanings of ‘what,’ ‘who,’ and ‘where’ that make the Internet such a beguiling topic.

The devices certainly have a presence. Surrounded by works of art and ornate decorations, they stand in stark metallic contrast with their environments. In several pictures there are parted curtains framing the mirror, lending to the Oz-esque sense that one’s witnessing the unveiling of the bulky machinery behind Google’s panopticon.

The cameras’ operators make occasional fuzzy appearances, despite being coached to avoid the mirrors and to position the camera so as to keep the equipment out of the frame.

In mirror-laden complexes like museums and opera houses, that’s not always possible.

These encounters represent wrinkles in the seamless virtualisation of our world that Google is trying to build. They take great pains to minimize them. In addition to blurring out bystanders’ faces, the algorithms are usually very effective at smudging away any trace of the equipment atop which the cameras are mounted (try looking straight down in Street View).

Google’s goal is to recreate a museum to exactness if possible so that people can go and see it just as if it were in real life. Having any sort of creases or instances shatters the illusion by seeing the machine that makes it. It takes people out of the experience, and makes them start to question what they’re seeing and wonder if it’s being displayed to them correctly.

In a sense, the images are pretty mundane.

Of course you’re not going to see yourself in the mirror using Google.The insight here is not some operational secret that Google has failed to cover up; instead, it raises questions about our place in the scene we occupy as users of this technology. When someone points over your shoulder and says ‘move over there’ in a Street View session, you’ll know what to do even if you don’t think about what ‘move’ or ‘there’ really means.

Still, Google seems genuinely interested in creating a representation of the real world that will ultimately cause those blurry conceptual borders to disappear entirely.

Today, GSV is already compatible with VR headsets, which Google is keen to get in front of as many eyeballs as possible. These glitches represent holes in the complete picture of the world it wants to paint, and you can bet that even these fluky gaps in the experience will be covered up.

Images like these represent the moment when exploring our world becomes a mediated experience. There isn’t necessarily anything to be worried about here, even if it’s somewhat creepy or unsettling. We’re at a transitional point with this technology, wherein reality is becoming augmented and simulated to bring us experiences we couldn’t have had before in places we might not otherwise be able to visit. In that sense, maybe we can see these Grand Inquisitors as our friends… or perhaps even as versions of ourselves. Either way, we should be paying close attention as this change takes place.

Ubiquitous Object Invisible Object reveals the self-censored workings of this all-seeing, all-knowing medium. The screenshots are rare glimpses of Google’s elusive “Street View” camera, busy at work, virtualising the interiors of different museums, castles, and institutions of power around the world. Unlike normal Street View though, in which Google’s car and camera have been easily masked out, the museums’ and castles’ plethora of mirrors present a situation where Google cannot cover its tracks.

These images are ambivalent portraits of the often invisible, panoptic power of Google’s observation.

In their place, alternatives, often virtual, have proliferated, designed to replicate and simulate these essentials. One such example is Google Arts and Culture, the omniscient search provider’s Street View-style virtualisation of museums and other cultural institutions.

It is meant to make the world’s treasures more accessible to all. In pursuing that goal, it has also inadvertently created windows into the strange interstitial space between our real and online worlds.

Wander past a mirror, and the sense of roaming a museum is suddenly shattered as you find yourself staring into the compound-eye of the machine behind the illusion.

Looking like Hal-9000 in high heels, the robot looking back holds the camera Google uses to capture the images it stitches together to recreate the museum, our unblinking vessel through the virtual world.

It embodies questions about the complex meanings of ‘what,’ ‘who,’ and ‘where’ that make the Internet such a beguiling topic.

The devices certainly have a presence. Surrounded by works of art and ornate decorations, they stand in stark metallic contrast with their environments. In several pictures there are parted curtains framing the mirror, lending to the Oz-esque sense that one’s witnessing the unveiling of the bulky machinery behind Google’s panopticon.

The cameras’ operators make occasional fuzzy appearances, despite being coached to avoid the mirrors and to position the camera so as to keep the equipment out of the frame.

In mirror-laden complexes like museums and opera houses, that’s not always possible.

These encounters represent wrinkles in the seamless virtualisation of our world that Google is trying to build. They take great pains to minimize them. In addition to blurring out bystanders’ faces, the algorithms are usually very effective at smudging away any trace of the equipment atop which the cameras are mounted (try looking straight down in Street View).

Google’s goal is to recreate a museum to exactness if possible so that people can go and see it just as if it were in real life. Having any sort of creases or instances shatters the illusion by seeing the machine that makes it. It takes people out of the experience, and makes them start to question what they’re seeing and wonder if it’s being displayed to them correctly.

In a sense, the images are pretty mundane.

Of course you’re not going to see yourself in the mirror using Google.The insight here is not some operational secret that Google has failed to cover up; instead, it raises questions about our place in the scene we occupy as users of this technology. When someone points over your shoulder and says ‘move over there’ in a Street View session, you’ll know what to do even if you don’t think about what ‘move’ or ‘there’ really means.

Still, Google seems genuinely interested in creating a representation of the real world that will ultimately cause those blurry conceptual borders to disappear entirely.

“We want to paint the world,” Google Maps’s Luc Vincent told the New York Times.

Today, GSV is already compatible with VR headsets, which Google is keen to get in front of as many eyeballs as possible. These glitches represent holes in the complete picture of the world it wants to paint, and you can bet that even these fluky gaps in the experience will be covered up.

Images like these represent the moment when exploring our world becomes a mediated experience. There isn’t necessarily anything to be worried about here, even if it’s somewhat creepy or unsettling. We’re at a transitional point with this technology, wherein reality is becoming augmented and simulated to bring us experiences we couldn’t have had before in places we might not otherwise be able to visit. In that sense, maybe we can see these Grand Inquisitors as our friends… or perhaps even as versions of ourselves. Either way, we should be paying close attention as this change takes place.

Ubiquitous Object Invisible Object reveals the self-censored workings of this all-seeing, all-knowing medium. The screenshots are rare glimpses of Google’s elusive “Street View” camera, busy at work, virtualising the interiors of different museums, castles, and institutions of power around the world. Unlike normal Street View though, in which Google’s car and camera have been easily masked out, the museums’ and castles’ plethora of mirrors present a situation where Google cannot cover its tracks.

These images are ambivalent portraits of the often invisible, panoptic power of Google’s observation.

︎︎︎

Note from the editor:

I’m in the Albertina museum. Weary legs morphed into left clicks, when, all of a sudden, I’m eye to eye with my mecha guide, draped thick in silver.

Ubiquitous Object Invisible Object (@_uo_io_), by Adrian Fernandez, presents a series of screenshots captured by Google Arts and Culture.A robot and its technician wander cultural institutions, archiving their insides.

It’s here we see, in Adrian’s words, “Google’s elusive ‘Street View’ camera, busy at work; virtualising the interiors of different museums, castles, and institutions of power around the world.”

He notes that, unlike normal ‘Street View’ where Google’s car & camera are censored; these museums’ and castles’ myriad mirrors frame a scene Google cannot obscure.