The Benevolent Asylum

By Aimee Howard

Benevolent

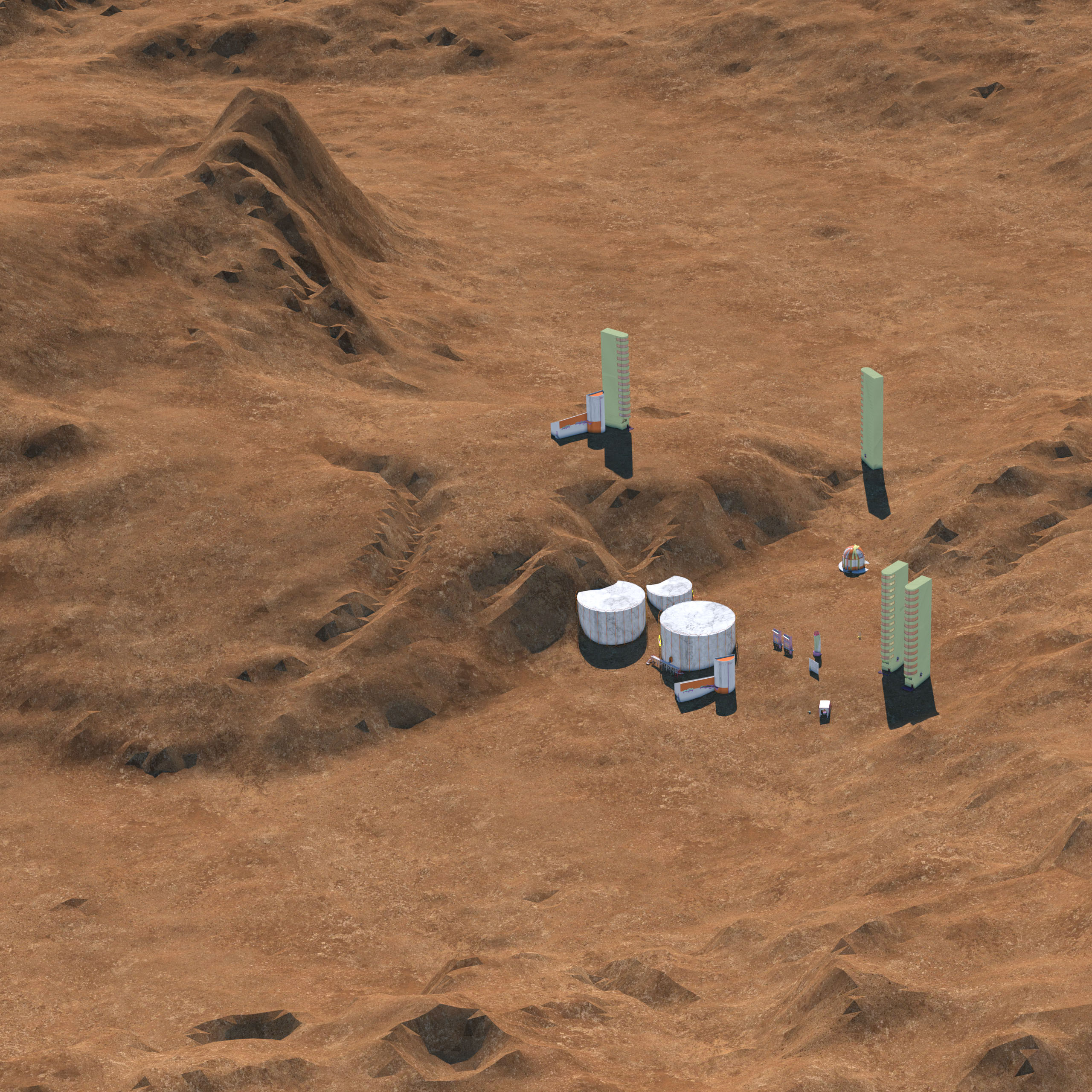

Asylum is an ironic reconceptualization of a project completed late last year

under the supervision of Simone Koch, mere months before the global pandemic

hit. The project comments on the eugenics associated with the institutionalisation of disabled and chronically ill people within the

Melbourne Benevolent Asylum in the early 1900’s. This project, although

completed prior to the pandemic, illustrates a glaringly relevant position in

today's climate. Through an examination of bias and misinterpretation,

especially from the perspective of a person with ‘underlying health

conditions’, this project attempts to reveal the ambiguous and absurd lines

between documented truth and fiction.

I have a myriad of auto-immune diseases that have touted me a high risk COVID-19 patient. Exacerbated by the widespread eugenics reported globally, I have come to accept the possibility of being denied health care over a ‘healthy’ person if I were to get infected. Acknowledging that whilst many are celebrating the loosened restrictions, anyone with a chronic illness and disability are required to be more vigilant, and further isolate from the community. It is exhausting and humiliating to constantly reiterate to those who refuse to listen, that our bodies will be disastrously affected by the actions (or inaction) of others. As I watch the majority of friends, family and colleagues return to their lives, myself and other high-risk people are forced further into isolation as we reap the consequences of a society returning to what they consider ‘normal’.

The notion of a Benevolent Asylum is an oxymoron. Benevolence, whilst intended to be well meaning, performs the role of a silent and complicit spectator whose emanation filters from failures of networks in control. Observing the asylum sparks a morbid curiosity in those who witness the quiet displacement of the narratives that inhabit this space. The Benevolent Asylum is not comforting, and it should make you feel unnerved.

The idea of being abandoned, isolated, and trapped is not new to those with disabilities and chronic illnesses, but none of this has been quite as distressing as the covert ableism from the community during this crisis. It is not news that the government and society devalue the sick and disabled, but I did naively expect more.

I have a myriad of auto-immune diseases that have touted me a high risk COVID-19 patient. Exacerbated by the widespread eugenics reported globally, I have come to accept the possibility of being denied health care over a ‘healthy’ person if I were to get infected. Acknowledging that whilst many are celebrating the loosened restrictions, anyone with a chronic illness and disability are required to be more vigilant, and further isolate from the community. It is exhausting and humiliating to constantly reiterate to those who refuse to listen, that our bodies will be disastrously affected by the actions (or inaction) of others. As I watch the majority of friends, family and colleagues return to their lives, myself and other high-risk people are forced further into isolation as we reap the consequences of a society returning to what they consider ‘normal’.

This project is an intimate exploration into the harsh reality of self-imposed isolation for a sick person, examining the expendable lives of those who are begging (and I do not use this term metaphorically) to live.

The notion of a Benevolent Asylum is an oxymoron. Benevolence, whilst intended to be well meaning, performs the role of a silent and complicit spectator whose emanation filters from failures of networks in control. Observing the asylum sparks a morbid curiosity in those who witness the quiet displacement of the narratives that inhabit this space. The Benevolent Asylum is not comforting, and it should make you feel unnerved.

The idea of being abandoned, isolated, and trapped is not new to those with disabilities and chronic illnesses, but none of this has been quite as distressing as the covert ableism from the community during this crisis. It is not news that the government and society devalue the sick and disabled, but I did naively expect more.

Note from the editor:

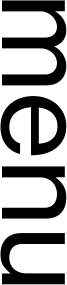

Aimee Howard’s work has always spoken with a unique creative

voice and hardly needs explanation, but enmeshed in this project, alongside

Howard’s distinctive aesthetic is a deeply personal and confronting political

message about the impact of the current pandemic on groups uniquely in danger. There

is a unique discomfort in this project and while it draws on Howard’s complex,

evocative project with Simone Koch, “Patent for an Exceptional City”, it

transcends it entirely.

An anxious displacement is developed between Howard’s writing and the luminous brightness of the images, hovering in that indeterminate space between eerie unreality and vicious reality.

We should linger here a while.

An anxious displacement is developed between Howard’s writing and the luminous brightness of the images, hovering in that indeterminate space between eerie unreality and vicious reality.

We should linger here a while.