Snapback

By Loughlin O’kane

Politicians have taken up a new buzzword of late… ’snapback’. The premise of this idea is that one day our society will wake up from its hibernation and return to the previously accepted normal. A myth that evokes the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty and holds about the same amount of reality. The long repercussions of this pandemic will be felt by all, especially those most vulnerable within our society.

It is undeniable that the repercussions of COVID-19 have presented a sizeable shift; psychologically, economically, and socially.

Much to the pleasure of the powers that be, it seems the idea of the ‘snapback’ has permeated through society. A longing for the old normal, in its total form, warts and all; perhaps it is longing for a time now passed, perhaps it is optimism, perhaps it is pessimism felt towards our ability to redefine the status quo despite its current suspension. In reality, this is foolhardy to believe. Nowhere has the lie of the snapback been unearthed more locally than in Melbourne. As we have made the retreat back to our houses, the long road to a way of being that looks and feels like before COVID-19 has gone from around the corner to the end of the M31. Our most basic interactions have been distanced, our faces are no longer to be touched, our friends no longer to be hugged and masks are to be worn. Fear of the other has become the status quo, not in that they themselves would hurt us, but more that they may be acting as an unwilling Trojan Horse for the virus.

This psychological shift is not easily reversed, let alone the broader economic and social changes. While our government stands by its position of not seeking eradication of the virus and the search for a vaccine continues, it is easy to see how our society will remain in its current state of fear and rightful cautiousness. That undoubtedly extends to our pocket of the world.

When we think of the virus it is almost impossible not to

think of it spatially, humans one and a half meters apart, four square meters

per person, ten people indoors, twenty people outdoors. The virus too has a

form, spiky, spherical and reminiscent of the seed capsule of a sweet gum tree.

Beyond the visual there is also an architecture to this virus; predominantly

defensive in nature. Compliance is sought at all levels, markings indicating

where to stand, where to circulate. We are constantly ushered by civic

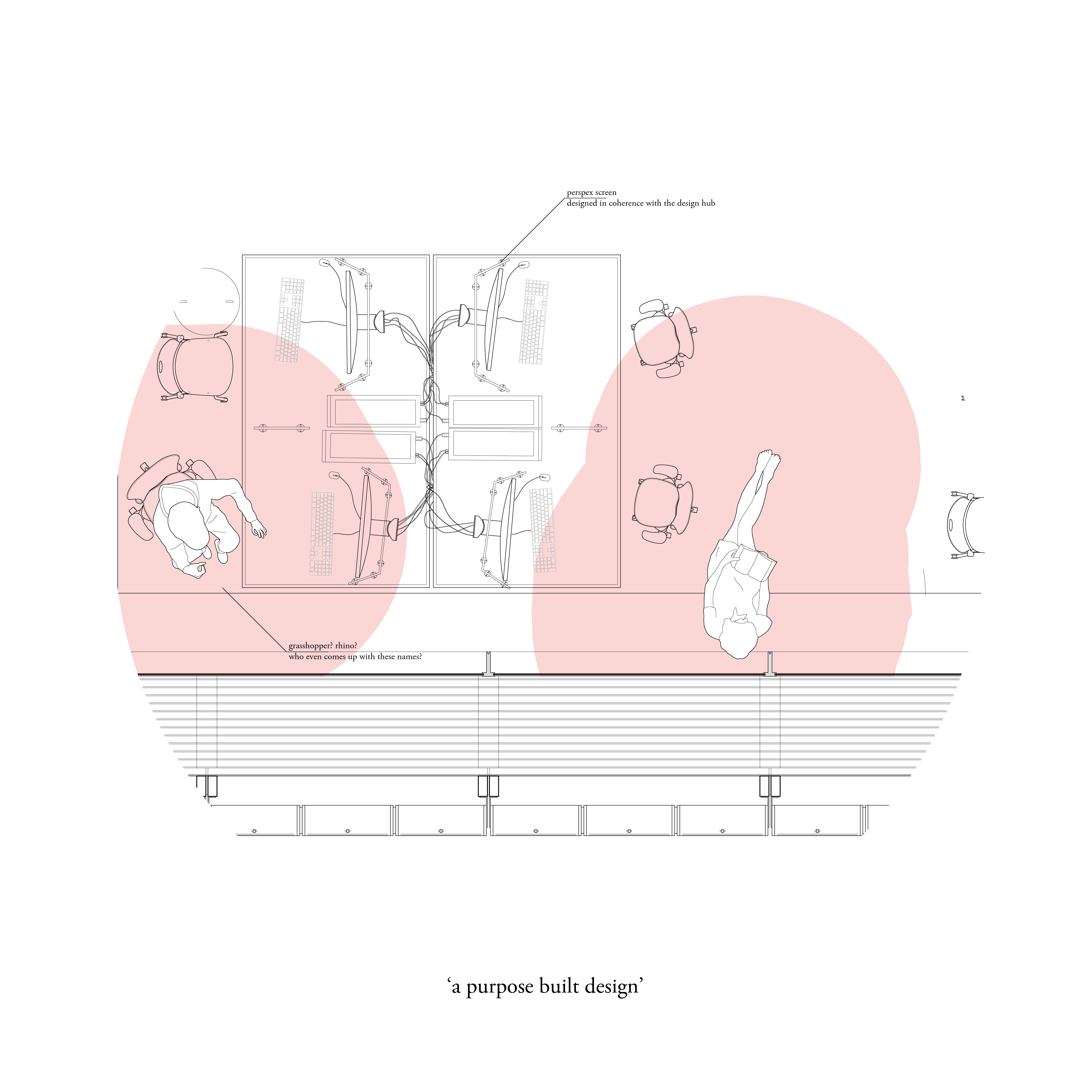

responsibility. Hand sanitiser stations are littered around and perspex is

ever-present, we are constantly reminded of the changing society we now find

ourselves in.

The architecture of the pandemic requires an active and

agile citizen.

Active, in that we are being told that it is us who need to act; to wash our hands, to maintain our distance, to stay home and not gather with our friends, family and colleagues.

Agile, in that we must be constantly perceiving the space surrounding us. Constantly monitoring others and subsequently acting. Agile, in that we must stay informed and responsive to the unfolding situation in front of us.

As we now begin to understand the pandemics manifestation in space it then becomes apparent that one of the foremost challenges facing RMIT Architecture is the eventual management of the return to the Design Hub.

Refitting? Refurbishment? Behavioural change? Almost certainly.

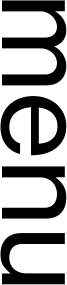

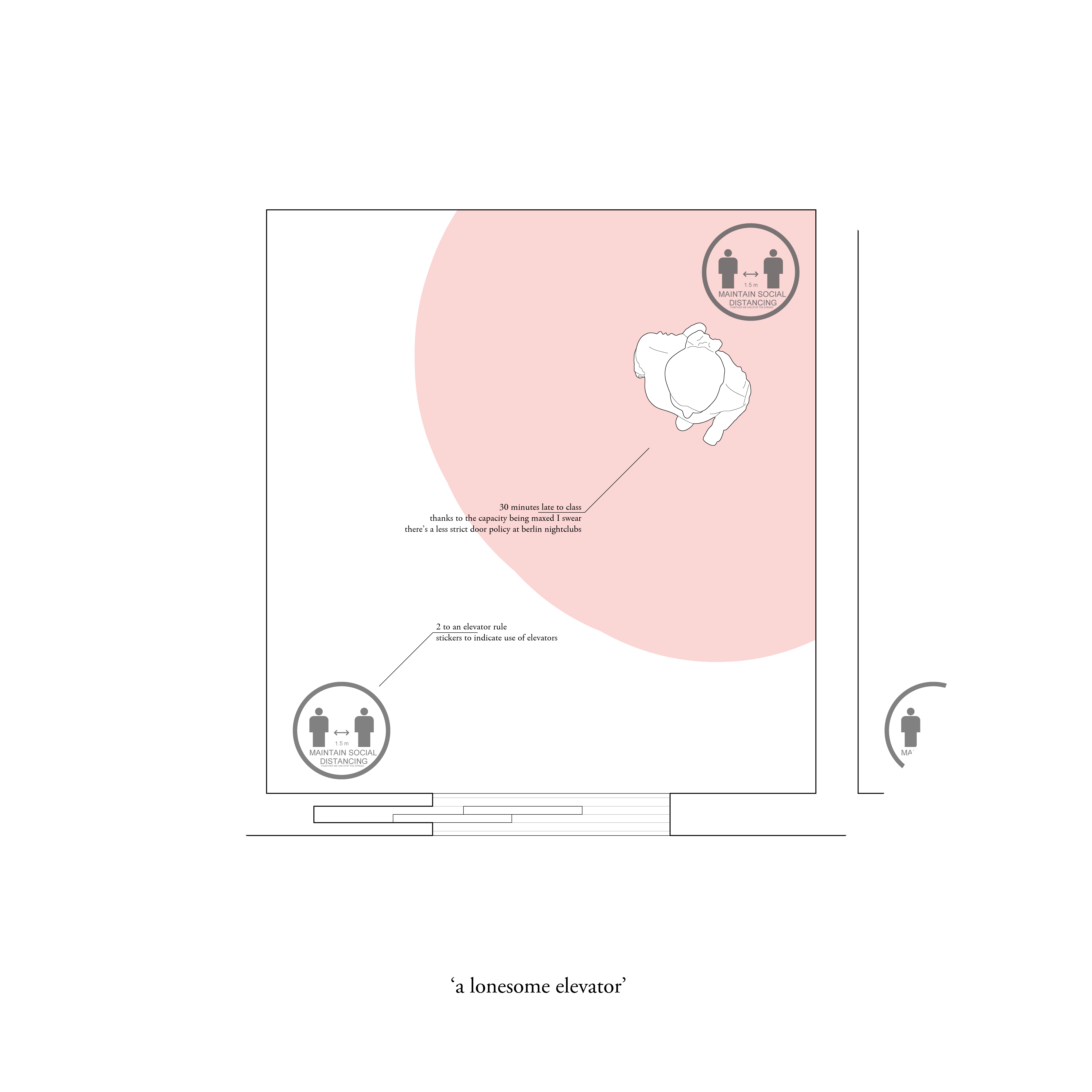

As those tasked with educating and learning the craft of interrogating space, it now seems relevant to put our collective space under inspection. What changes to our environment will the school have to undertake to keep us safe? The kitchenettes will most likely be closed, the lift will have dots indicating where to stand. Perspex screens will line the computers, undoubtedly designed in coherence with the rest of the Design Hub. The already overpopulated building will have a capacity limit, your temperature may be scanned via a thermal camera upon entry, despite its inaccuracy1. Surfaces will have the pungent smell of sanitiser, especially over the emblematic steel surfaces of the Design Hub that have been proven to sustain the virus for up to seven days2.

The architecture of the pandemic requires an active and

agile citizen.

Active, in that we are being told that it is us who need to act; to wash our hands, to maintain our distance, to stay home and not gather with our friends, family and colleagues.

Agile, in that we must be constantly perceiving the space surrounding us. Constantly monitoring others and subsequently acting. Agile, in that we must stay informed and responsive to the unfolding situation in front of us.

As we now begin to understand the pandemics manifestation in space it then becomes apparent that one of the foremost challenges facing RMIT Architecture is the eventual management of the return to the Design Hub.

Refitting? Refurbishment? Behavioural change? Almost certainly.

As those tasked with educating and learning the craft of interrogating space, it now seems relevant to put our collective space under inspection. What changes to our environment will the school have to undertake to keep us safe? The kitchenettes will most likely be closed, the lift will have dots indicating where to stand. Perspex screens will line the computers, undoubtedly designed in coherence with the rest of the Design Hub. The already overpopulated building will have a capacity limit, your temperature may be scanned via a thermal camera upon entry, despite its inaccuracy1. Surfaces will have the pungent smell of sanitiser, especially over the emblematic steel surfaces of the Design Hub that have been proven to sustain the virus for up to seven days2.

The

cleaners will be omnipresent rather than relegated to the night shift. The

Design Hub itself is entirely mechanically ventilated; mechanical ventilation

as a system has been linked to an outbreak in Guangzhou, China where a table

approximately six metres away was infected3,

these systems will have to be managed. Behaviourally the students and staff

will have dramatic shifts in interactions. We will stand distanced, a cautious

nod or elbow bump will be the extent of our greeting. Face masks will be worn.

Our patience too will be tested, lines for the printer will snake through the

building with students standing the regulated distance apart. A wait time may

even be extended to the entry due to the capacity limit. However they manifest,

changes will occur. The responsibility for change will fall at both the feet of

the university and the users of the building, for if either group falters then

the viability of the operation will be placed in jeopardy. Lying in our path is

a shift potentially as great as moving learning online.

Be ready to return, but don’t expect a snapback..

[1] Bucknall, T., 2020. Are Thermal Cameras A Magic Bullet For COVID-19 Fever Detection? There's Not Enough Evidence To Know. [online] The Conversation. Available at: <https://theconversation.com/are-thermal-cameras-a-magic-bullet-for-covid-19-fever-detection-theres-not-enough-evidence-to-know-139377> [Accessed 12 July 2020].

[2] Chin, A., Chu, J., Perera, M., Hui, K., Yen, H., Chan, M., Peiris, M. and Poon, L., 2020. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. The Lancet Microbe, 1(1), p.e10.

[3] Lu, J., Gu, J., Li, K., Xu, C., Su, W., Lai, Z., Zhou, D., Yu, C., Xu, B. and Yang, Z., 2020. COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with Air Conditioning in Restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(7), pp.1628-1631.

︎︎︎

Note from the editor:

In a concerning way, Loughlin O’Kane’s project, Snapback, feels eerily prescient. There is no doubt that the future he proposes could come to pass. But more than that, O’Kane’s detailed satirical drawings call attention back to the implications of this crisis on RMIT Architecture’s institutional home, the much lauded and much maligned Design Hub.

While his tone remains light, the drawings technical more than polemical, O’Kane’s strong political instincts center on the duty of care that RMIT Architecture has to their students. How can the financial and political requirements of the university sector, a sector that has been brutalised by the economic effect of COVID-19, respond to their institutional duty of care to their students? In the same stroke, O’Kane contrasts the institutional responsibility of the university with the personal ethical responsibilities we all maintain towards public health. As we enter another period of what is sure to be a long series of heightened anxieties and ever more present restrictions and modifications to behaviour, it is imperative that we can clearly examine our own responsibilities and the responsibilities of those institutions to which we belong.

Economically and socially it is clear that there will be no clean return to normalcy, the deterritorialising effects of global crisis might not be entirely brought back into the territory of capital. But, in O’Kanes work, the spatial and architectural circumstances of our return are imagined and drawn in incontrovertible detail.

Should we return at all…

Note from the editor:

In a concerning way, Loughlin O’Kane’s project, Snapback, feels eerily prescient. There is no doubt that the future he proposes could come to pass. But more than that, O’Kane’s detailed satirical drawings call attention back to the implications of this crisis on RMIT Architecture’s institutional home, the much lauded and much maligned Design Hub.

While his tone remains light, the drawings technical more than polemical, O’Kane’s strong political instincts center on the duty of care that RMIT Architecture has to their students. How can the financial and political requirements of the university sector, a sector that has been brutalised by the economic effect of COVID-19, respond to their institutional duty of care to their students? In the same stroke, O’Kane contrasts the institutional responsibility of the university with the personal ethical responsibilities we all maintain towards public health. As we enter another period of what is sure to be a long series of heightened anxieties and ever more present restrictions and modifications to behaviour, it is imperative that we can clearly examine our own responsibilities and the responsibilities of those institutions to which we belong.

Economically and socially it is clear that there will be no clean return to normalcy, the deterritorialising effects of global crisis might not be entirely brought back into the territory of capital. But, in O’Kanes work, the spatial and architectural circumstances of our return are imagined and drawn in incontrovertible detail.

Should we return at all…