The Rub: Systems of Preservation and Progress in Architecture

By Leon Koutoulas

Supervised by Dr. Michael Spooner

Supervised by Dr. Michael Spooner

This project began primarily concerned with two things: preservation and progress. However, it became increasingly evident that whilst my interest lies between these two conditions, it is focussed on the point at which both can simultaneously exist, hypothesising a potentially productive crisis.

THE MYTH: HINTING TOWARDS CAPACITY

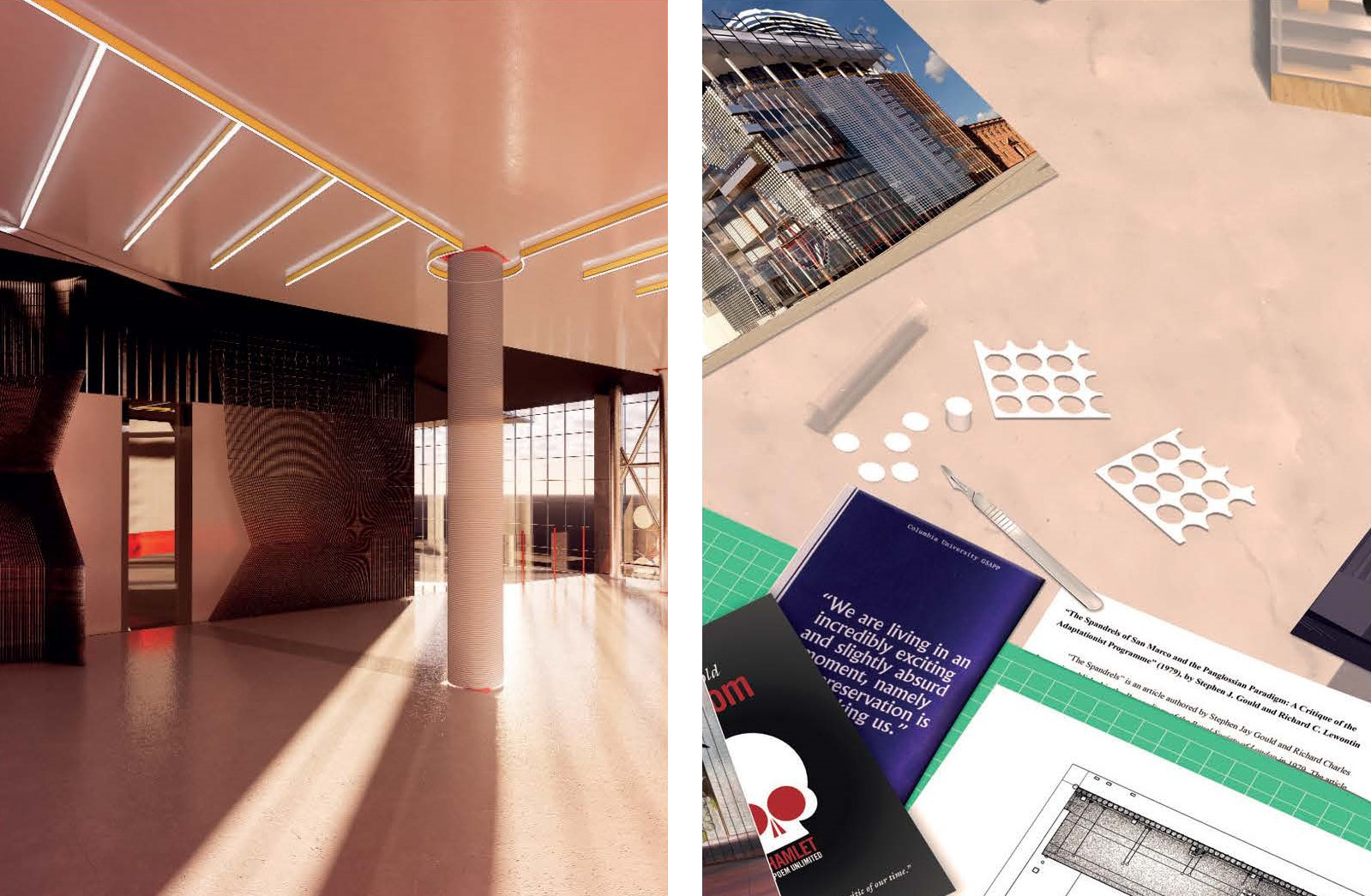

In “Hamlet: Poem Unlimited”, Harold Bloom explores how Shakespeare’s experiences at the time of writing influenced his eponymous protagonist. John Hejduk speculates that one of those experiences was witnessing the Globe Theatre deconstructed, transported across the River Thames, and reconstructed as an exact copy.

He identifies that it was this action, where the playwright was able to witness the architectural artifice deconstructed and reconstructed, that enabled him to conceive of Hamlet; a character who deconstructs and reconstructs himself, the play in which he exists and the world outside of that play.

In other words, not only does he interrogate his own ‘globe’ (his head), but also The Globe as theatre and the Globe as life beyond the confines of drama.

Out of architecture is born a self-perpetuating crisis; a character anxious to preserve himself, whilst just as anxious to move forward with decisive action. Hamlet’s indecision causes a maelstrom, forcing the world around him to shift and respond to his contemplations, provoking action for good or bad.

Through the manipulation of our formal language (The Globe Theatre), we see an apparatus emerge, capable of the most sublime contemplations on our most intractable human dilemmas. This possible capacity of architecture is where this project founds itself – in a myth, following nothing but a hint towards our ability, with our language, to take on lofty contemplations.

SYSTEMS OF PRESERVATION AND PROGRESS IN ARCHITECTURE: STAYING ON TOPIC.

If nothing more than death and damage comes from his contemplations, Hamlet’s action (or inaction) has a saving grace - it does not let us forget the question. The same can be said for the following systems outlined. Observed from architectural precedents, each system describes a formal condition in which the present and the past are intricately woven to create an object which bears the ‘whips and scorns’ of contemplation.

Within the framework of the project, this provides the basis for shift, whereby the ‘crossing of the Thames’ is replayed in hope of some Hamlet-esque emergence. As the Hamlet does his head, and Shakespeare does his Globe, this project interrogates its own realm of existence: the RMIT School of Architecture.

‘…Perchance to dream’:

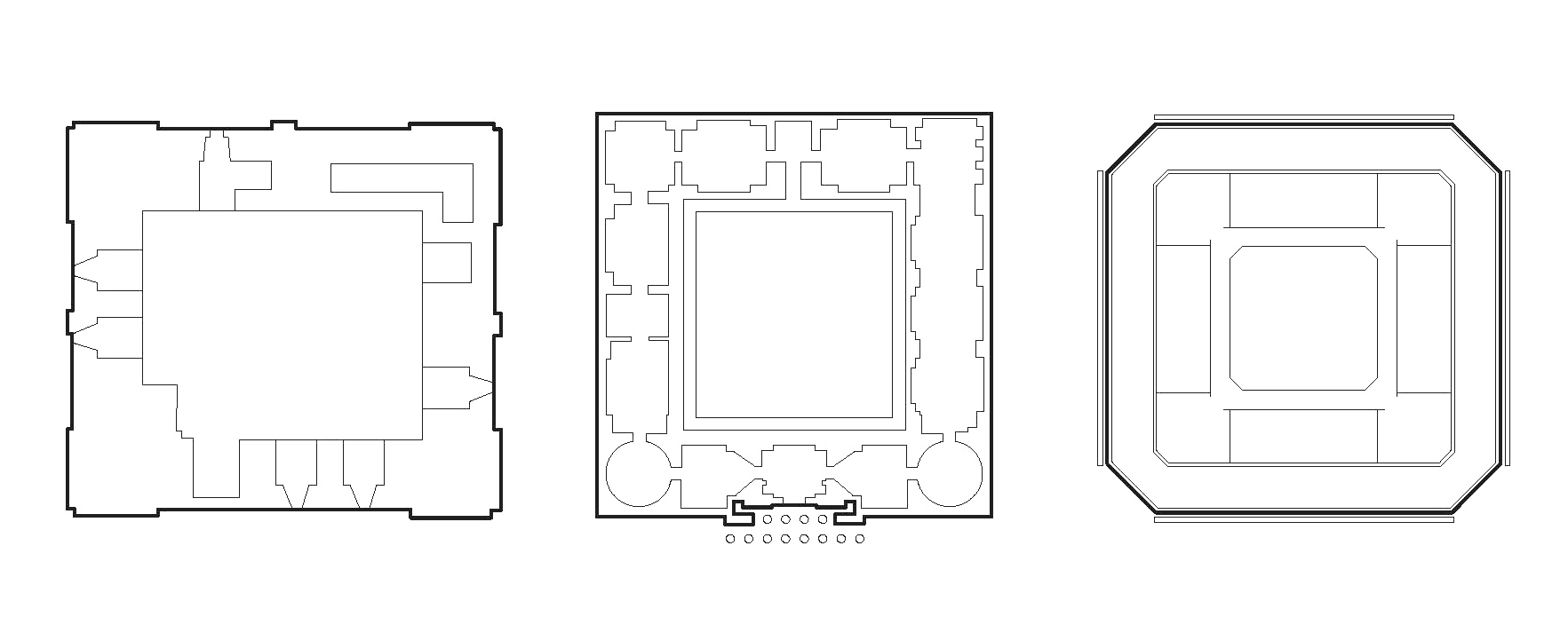

ONE / Encasement

System: The construction of an additional structure which entombs an original, not only preserving it, but fundamentally redefining its relationship with the context.

Example: The Coops Shot Tower, designed in 1889, is encased in a glass cone by Kisho Kurakawa as part of the Melbourne Central development one-hundred years later, redefining the city’s understanding of the original structure.

Translation: Here, the original Design Archives building can be seen encased as a precious original, preserved as a past condition but repurposed as a new entry to the basement. Already absorbed into the larger Design Hub box, the original archive building also sits within its own ‘glass cabinet’, making it difficult to discern whether the original archive building is now simply a symbolic remainder of a prior use, or whether it still forms a functioning part of the archive. Its relationship with its context is thereby confused, as it becomes a building encased within an encasement; a play within a play if you will.

TWO / Suspension

System: An existing structure is included into a series of subsequent structures. Despite the subsequent structures being destroyed, the original piece of architecture is maintained (at least in part) and thereby preserved.

This creates a system whereby any new design needs to negotiate the original structure, holding the past and the present in adjacency.

Example: The University of Melbourne MSD building by John Wardle is the most recent version of a series of designs which included and preserved the old Joseph Reed Bank of NSW facade. Whilst the building behind the facade tends to dissolve every few decades, the bank facade persists.

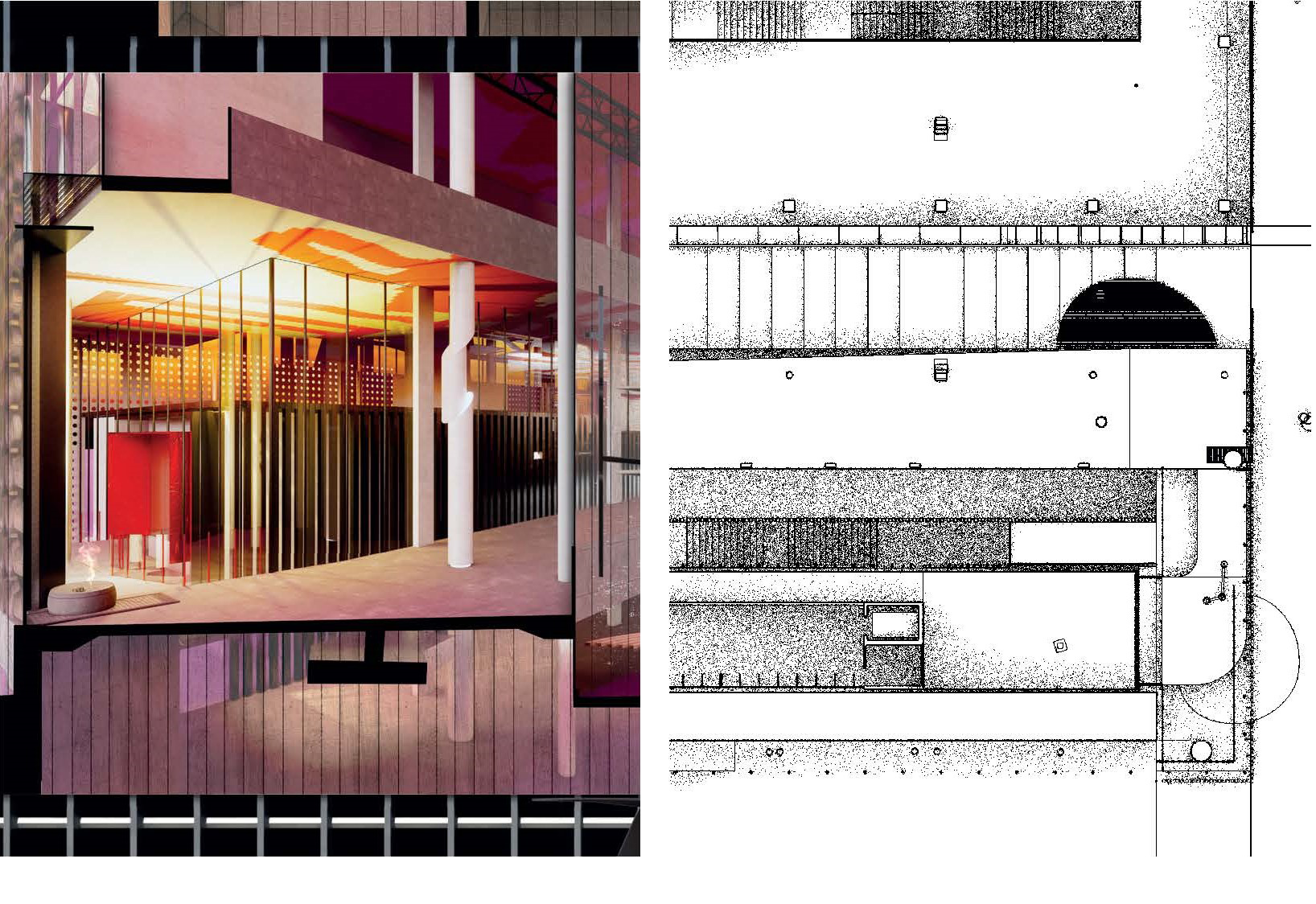

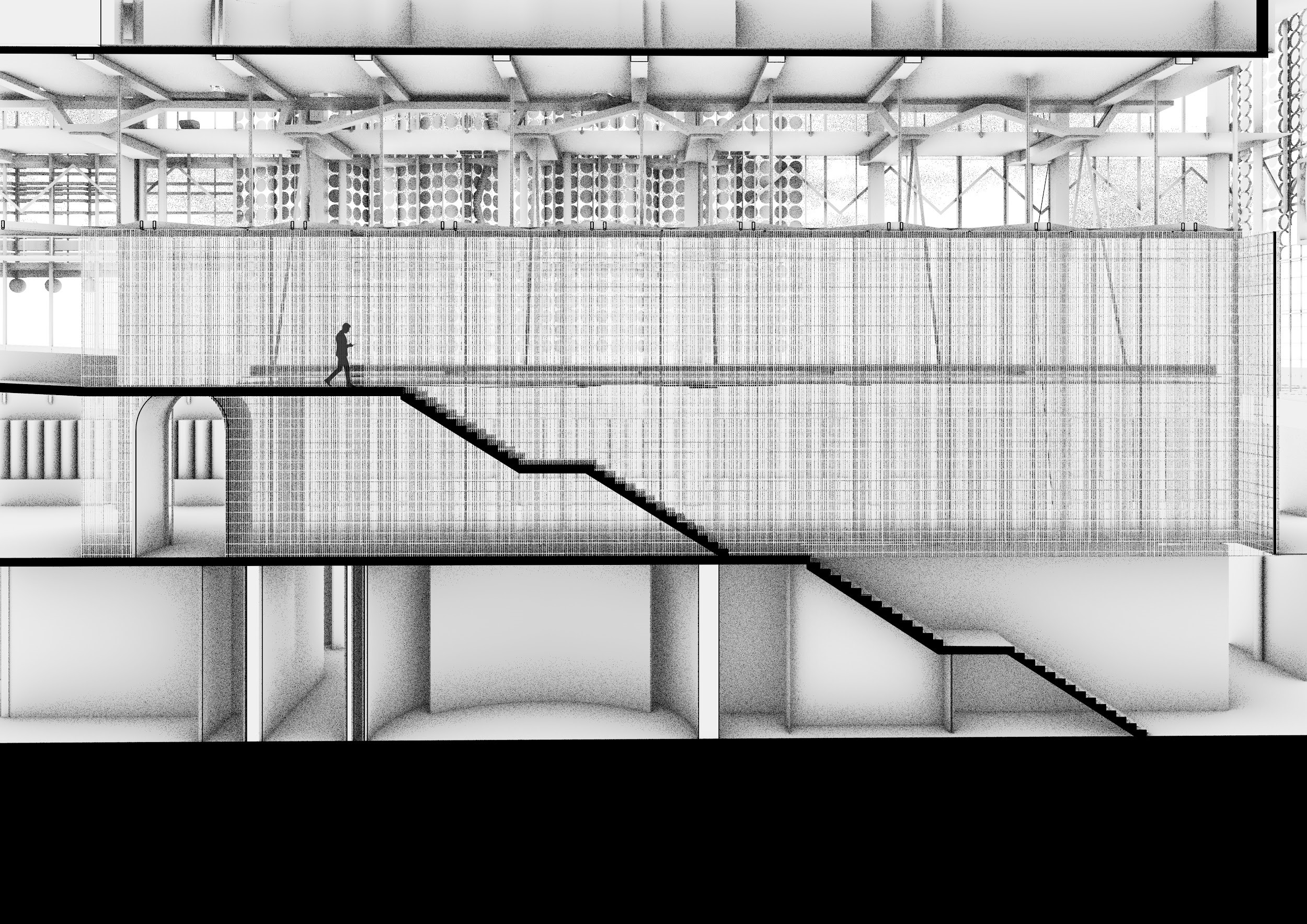

Translation: The design hub stair, which stretches from the foyer level to the level one basement in one long line, remains, despite the rest of the building being shifted across. Becoming a primary point of entry off street level, the stair is held in space and exposed not only to those traversing them, but also those adjacent.

Nothing remains but the floor and the web forge, making the entry an experience of the building's most definitive materials.

THREE / Envelope by title

System: Envelope by title describes the capacity for a building title (usually an institutional title) to automatically include the original structure and any subsequent structures on a given site. These envelopes are invisible, although can be manifested physically if a site is built out to its extents.

This system claims the past, the present, and usually the future of a site – giving it the capacity to hold all tenses at any given time. Often too these systems can be legislative, bringing about a particular kind of permanence which can surpass that of any architecture.

Example: The State Library of Victoria is a well-known agglomeration of 22 separately constructed buildings, claimed under the title ‘State Library of Victoria’.

This title envelopes all 22 structures and claims any future structures to be built on the site.

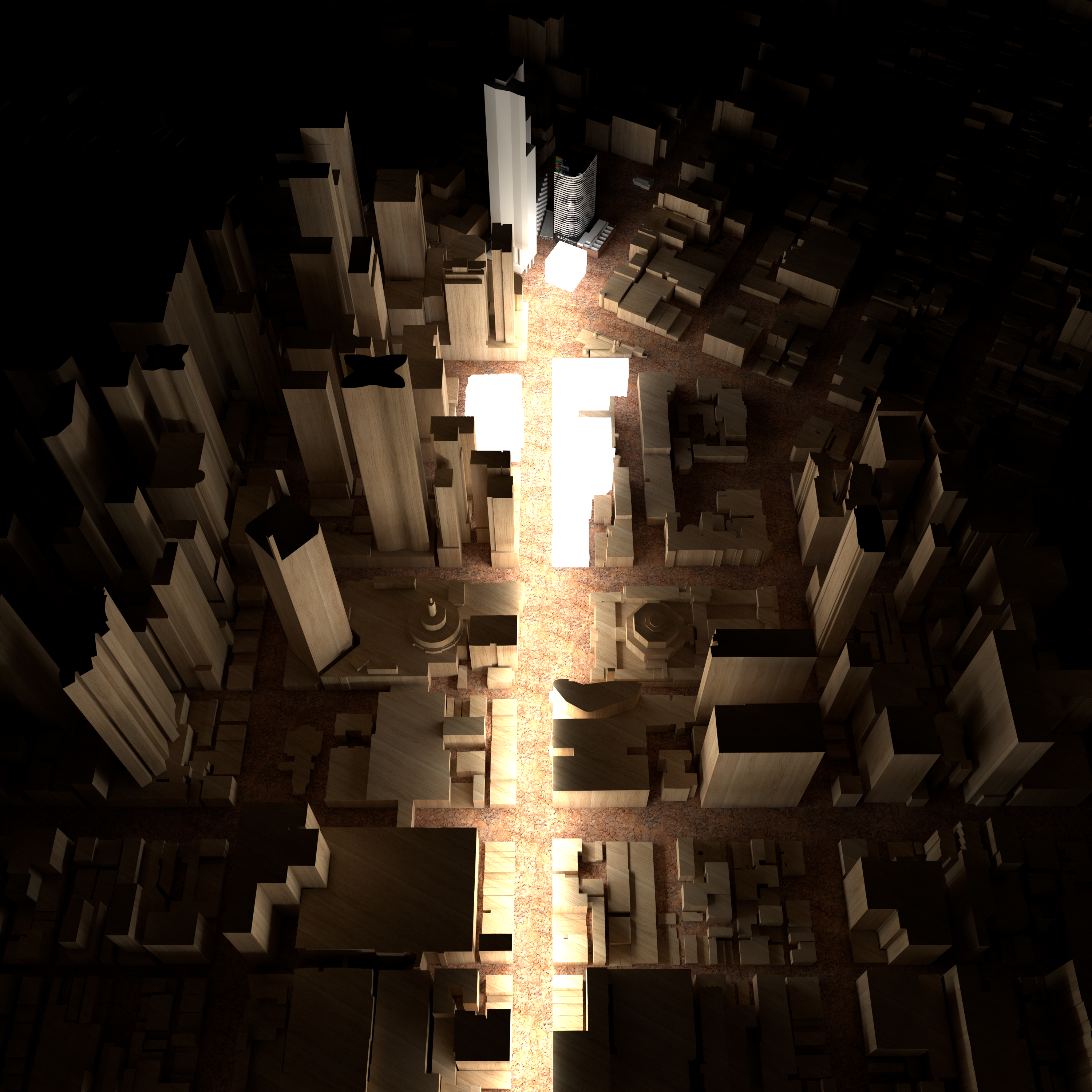

Translation: Already claimed under an institutional title, the RMIT Design Hub is part of a string of pedagogical buildings that run up the Swanston St axis. Uniquely positioned as the architecture school, the building is acutely aware of its own existence and the means by which it has been procured.

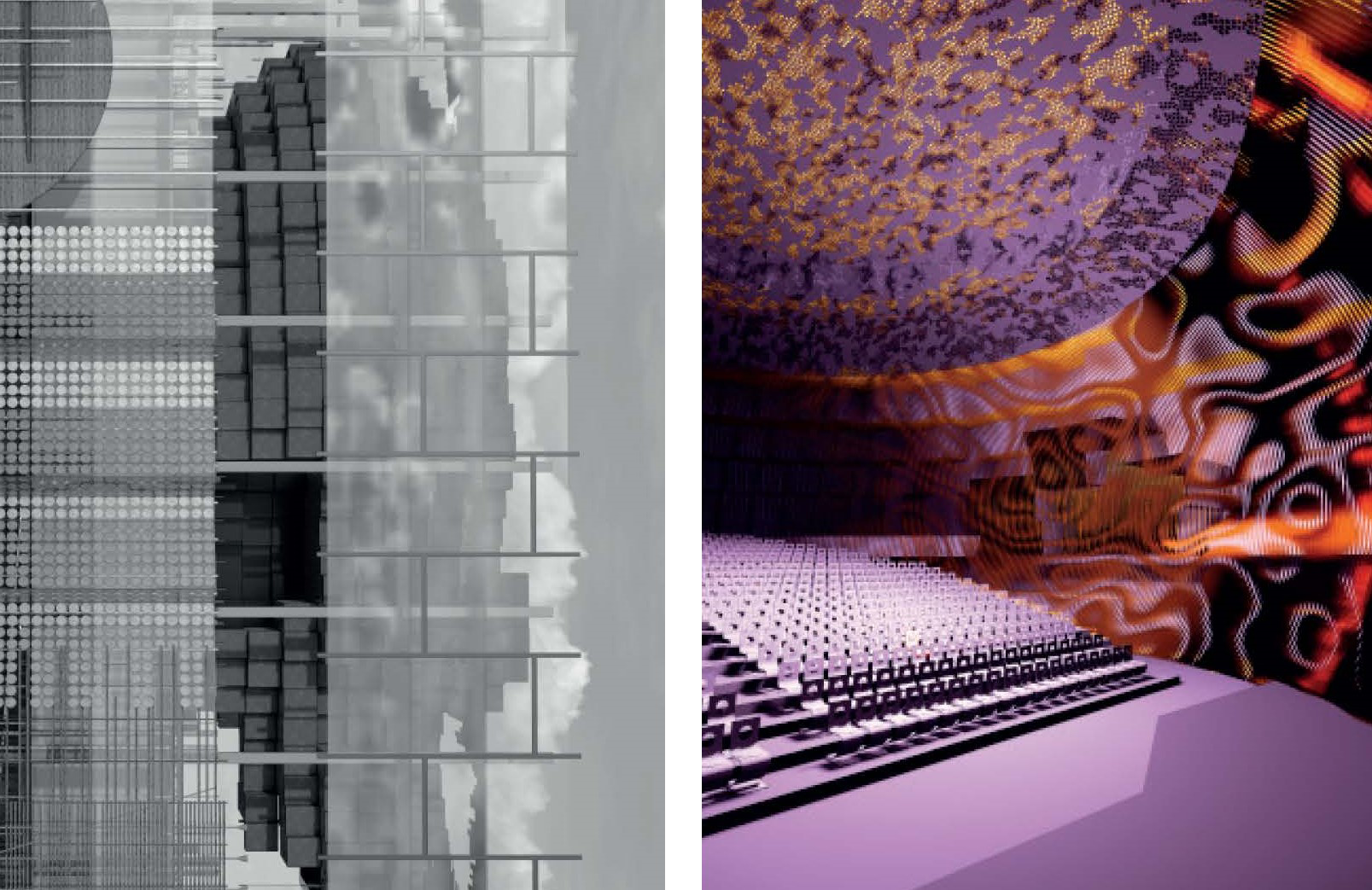

Sitting just outside the Hoddle grid, the Design Hub peers back from the edge of the envelope, each student and teacher understanding that their view of the school is both elevated and obscured, knowing a little too much to ever be fully absorbed. Everything now is known through the quatrefoil, or in the warped reflection of a convex window, or in Godsell’s finally realised spherical cells.

“He (Hamlet) knows that he knows more.” - Harold Bloom

FOUR / Envelope by Structure

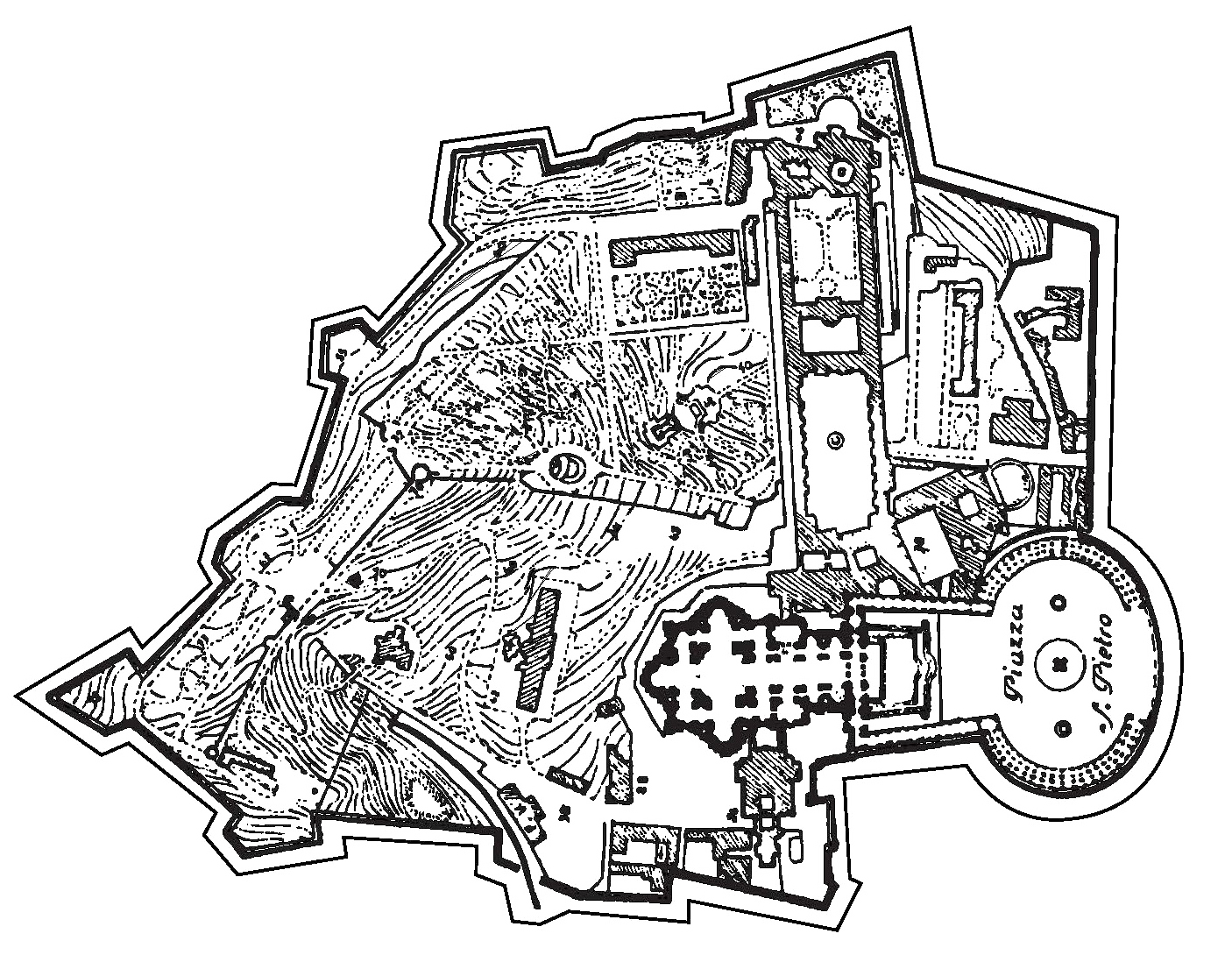

System: Envelope by structure describes a condition in which a portion of land is defined by a physical boundary. Often a defensive structure, this boundary sees to the maintenance or preservation of a collection of structures within. The collection is able to morph and change whilst still being defined as part of a larger grouping. Any alterations or additions to the existing structure is automatically claimed and held together within the boundary.

Example: Vatican City sits within the larger civic context of Rome but claims itself as a separate entity. This portion of land is physically defined by the Vatican City wall, which indiscriminately claims all past, present, and future structures as part of a larger whole. Interestingly, this physically defined portion of land is representative of a much larger grouping under the title of ‘Catholic’, which can be defined under the previous system ‘Envelope (by title)’.

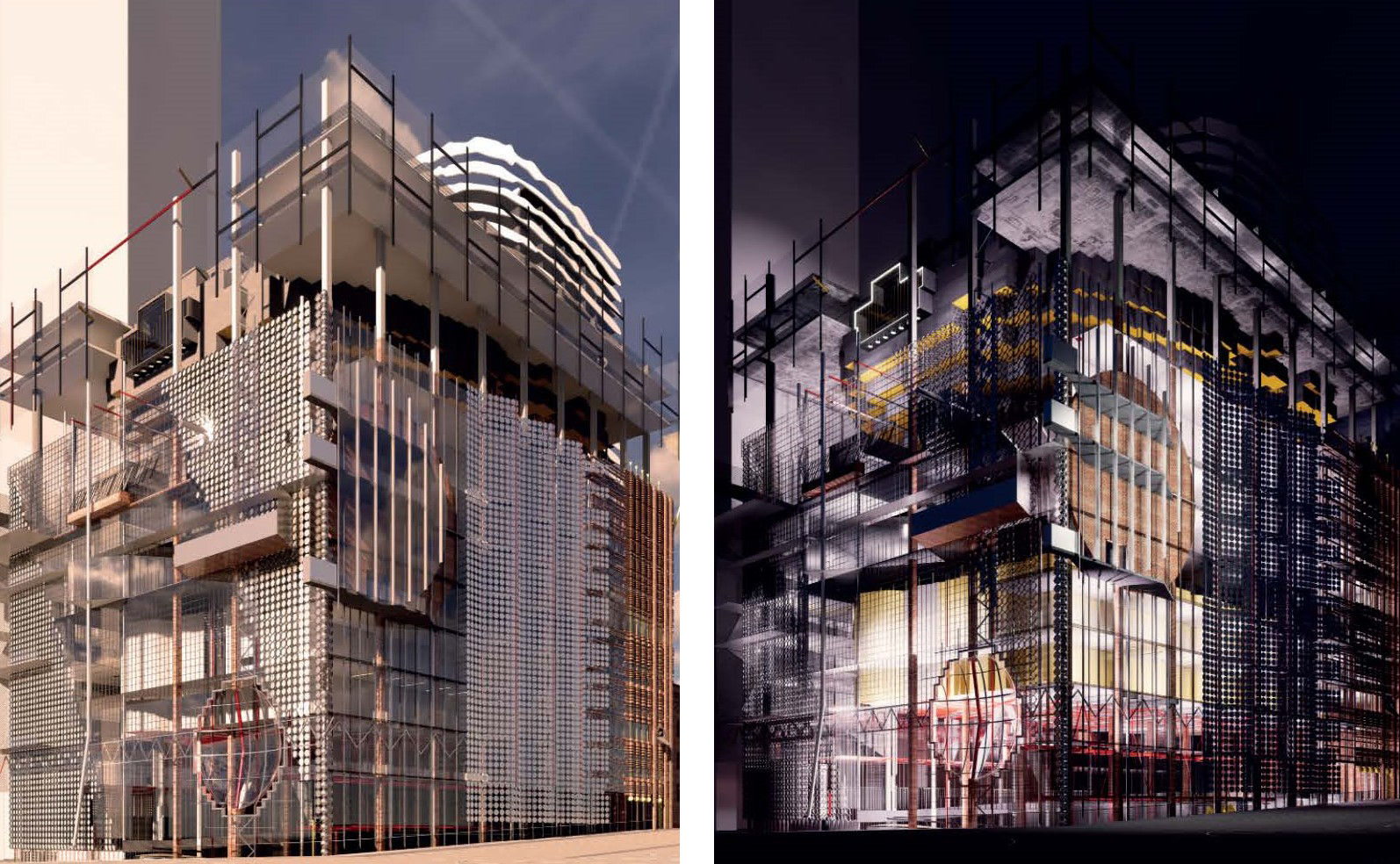

Translation: The envelope of this building not only defines a boundary but acts as a surface to perform preservation. It attempts this through performance; absorbing the world around it, whilst projecting the world within. It is a kind of schizophrenic mediator; altered in parts with surgical precision, maintaining beyond anything else the need to preserve some elements of history for some time.

This, in the hope that a similar condition will be maintained within. Imagine Batholomew by Marco d’Agrate only half revealed.

“The wounded surgeon plies the steel that questions the distempered part.” - T.S. Eliot

FIVE / Mimesis

System: The imitation of historical architectural systems as a means of preservation. This usually results in a somewhat perverted version of the original system as it is used for something other than its original purpose.

Example: A clear relationship can be seen between Castle Hedingham in Essex, The Glyptothek Museum by Leo Von Klenze and the Philips Exeter Library by Louis Kahn. Through the mimicry of spatial conditions, these three buildings (along with many other historical precedents) represent three disparate periods of architecture. These similarities occur despite period, style, program or location.

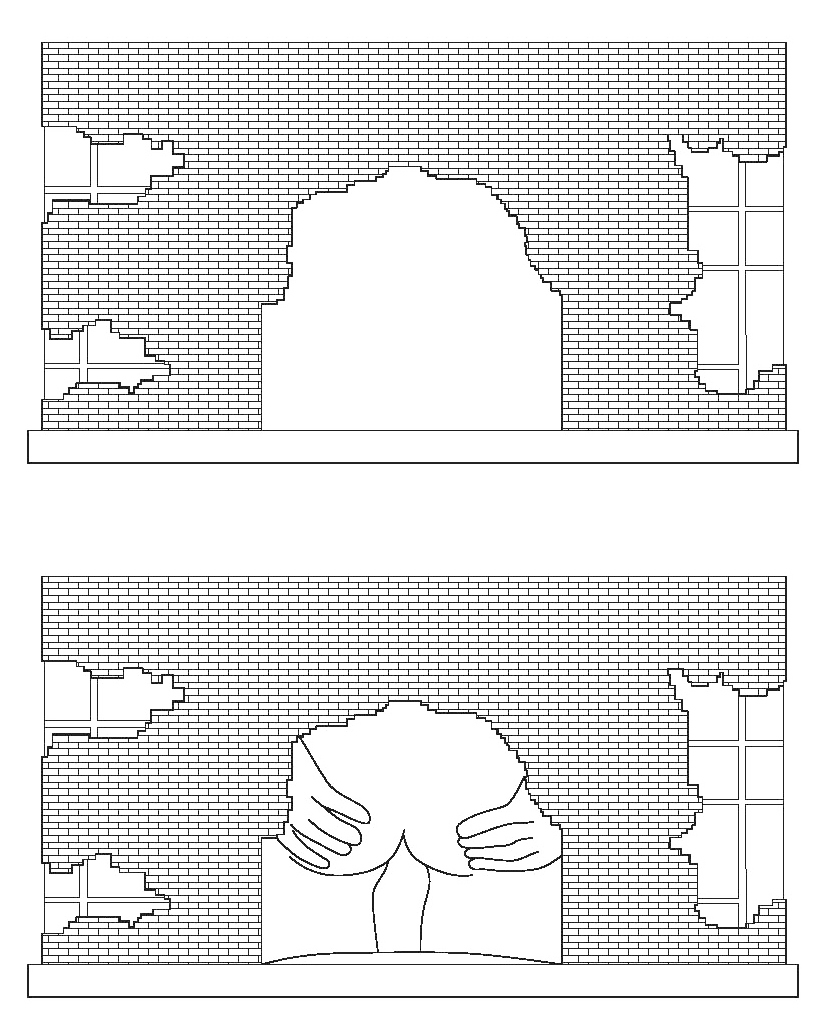

Translation: Through the act of mimicry, this project can be understood as something which preserves memory. However, the most interesting outcomes have occurred where there has been a linguistic stutter, making something new from multiple layers of different histories. The circular window sitting adjacent to the CUB Maltore and the languages embedded within many of Swanston Street’s prized buildings have been collected to form a single negative bay window. A single disc is rotated to form an arch, cut into by a single penrose tile, shaded by flaps far too similar to those which adorn the SAB. A new window emerges which is less mimesis and more collation.

“Distracted from distraction by distraction...” - T.S. Eliot

SIX / En Mass

System: A structure preserves itself through sheer size or quantity.

Example: The Melbourne Goods sheds are heritage listed sheds near the Docklands. During the redevelopment of Docklands, it was argued that because the sheds are so large, they can withstand alteration without compromise to their heritage value. The sheds here are seen to preserve themselves despite the extension of Collins Street, and now exist as a remnant of history whilst also enabling progress.

Translation: This building already exists ‘en mass’ twice over. Firstly, by its unapologetic rigidity which is extraordinarily difficult to break. Secondly, and more importantly, by the sheer mass of discs necessary for its facade. After an unfortunate situation which called for the replacement of all glass discs, there remained the original, and now redundant, 16,000. Not wanting to dispose of this much original history, my project repurposes the 10-millimetre-thick discs into 160 metres of glass column to be distributed as needed.

“Consider the future and the past with equal measure.” - T.S. Eliot

SEVEN / Transplantation

System: The preservation of a structure through its movement from one site to another. Usually this occurs when a structure is under threat in its original location and results in slight alterations during transportation.

Example: St James Cathedral, Melbourne’s oldest church, was transplanted from its original site near the corner of Collins St and William St, to its current site, in an effort to protect the structure from being lost. During the process it lost a row of stone from its tower and a foot of length in the nave. It now exists as a remnant of Melbourne’s History but also as a result of the preservative measures taken to maintain that history.

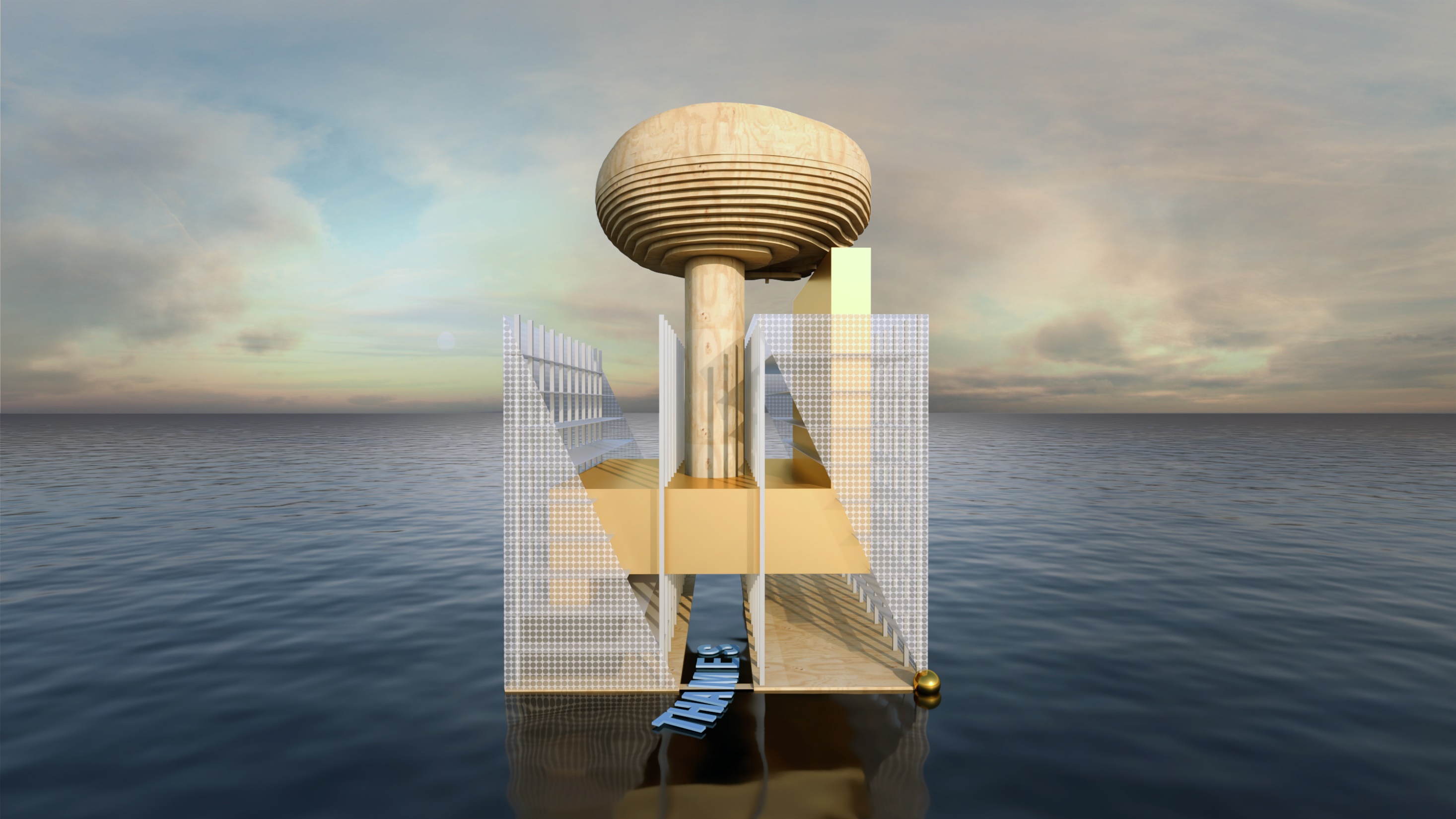

Translation: In this image the original object sits half rebuilt, hanging over its own transfigurative Thames. Beyond the encasement of the original archive building, this manoeuvre works to split the core of the original building and requires a bridging between the upper and lower half. This bridging becomes the archive storage which the building's inhabitants are now forced to encounter and acknowledge. It is these types of emergent alterations which transplantation seeks to provide.

“It tosses up our losses the torn Seine.” - T.S. Eliot

EIGHT / Healing

System: The use of additional architectural interventions in order to suture damaged or unresolved architectural fabrics. This usually requires careful consideration, and quite often can negotiate the space between two or more disparate architectural periods or styles.

This intervention, like any good suturing, should seek to maintain the original structure as much as possible, ultimately becoming part of the structure and making it difficult to understand the original building without its additions.

Example: Castel Vecchio by Carlo Scarpa sees two Veronese palaces stitched together through a series of highly considered interventions, healing the damaged portions of the existing structure and preserving the original architecture. The building is now more renowned than the original structure was, making it difficult to discern whether the value lies in the original or its preservative measures.

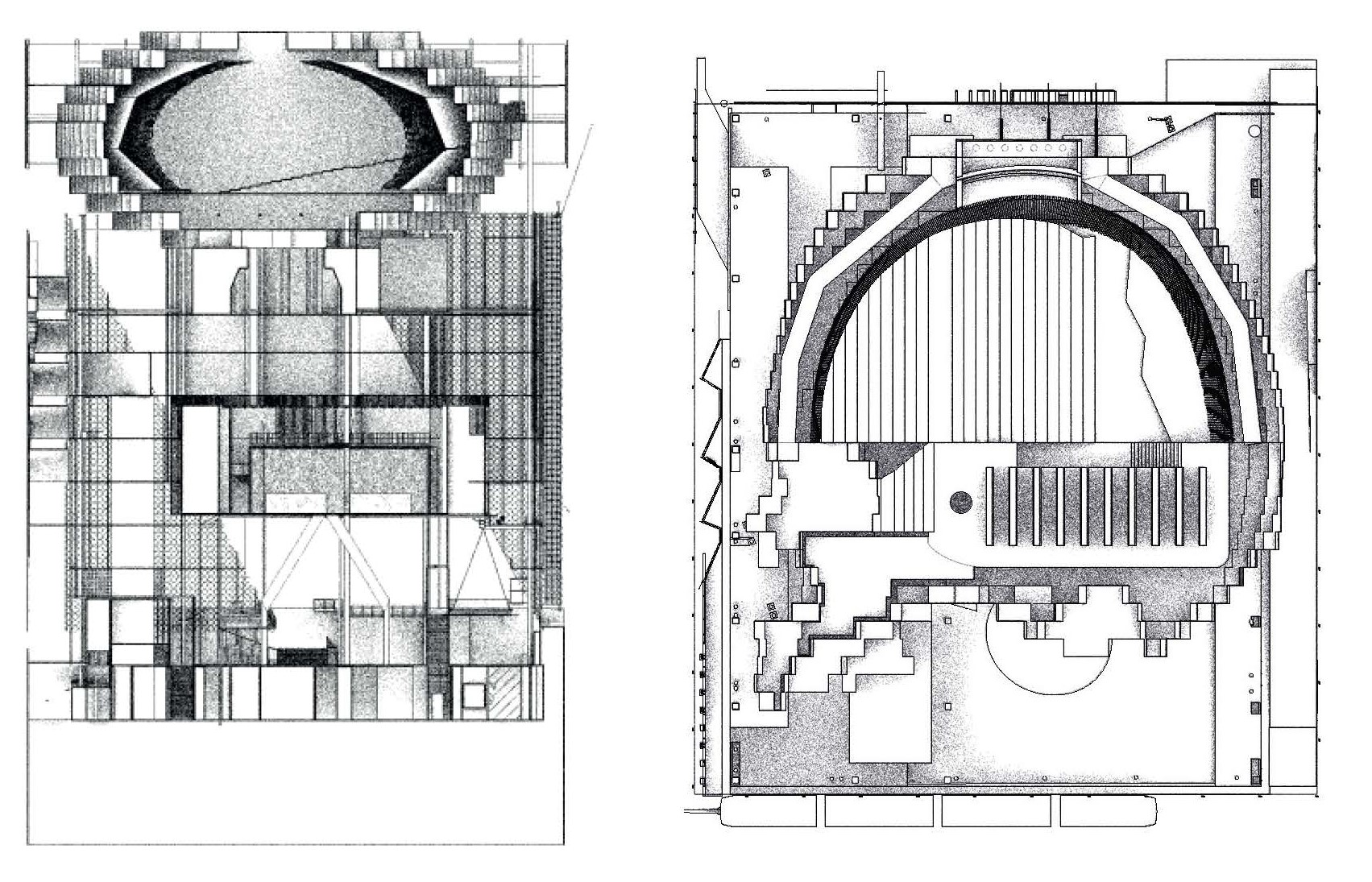

Translation: Healing is described as an ability to prolong the existence of a building, bringing it into the future. Where there is no natural state of dilapidation one must be created so to create the conditions for healing. In this project, the archive walls are battered by the rotation of the structural grid which twists to match the Hoddle. Each ‘whip and scorn’ is then treated and used for various spatial opportunities. The structure is ‘treated’ rather than being rebuilt.

“The sharp compassion of the healer's art.” - T.S. Eliot

NINE / Corrective Measures

System: An alteration is made to a system while the other properties are maintained. The alteration may or may not be a correction, it doesn’t matter, as long as the architect believes it is so.

Example: Mies van der Rohe and Phillip Johnson both adhere to the same basic principles, maintaining the essence of radical modernism in their work.

However, in the interior, Mies uses a gridded system of planning while Johnson introduces a foreign system, making each of their projects unique.

Translation: The gallery space is rethought according to the proportions of the Laurentian Library, as aspired by Sean Godsell in earlier iterations of the foyer. However, the proportions are made ‘more correct’, holding the ceiling and the floor at equal distances. This system preserves Godsell’s intentions for the building, while also creating a new space.

“Something is rotten in Denmark.” – Hamlet

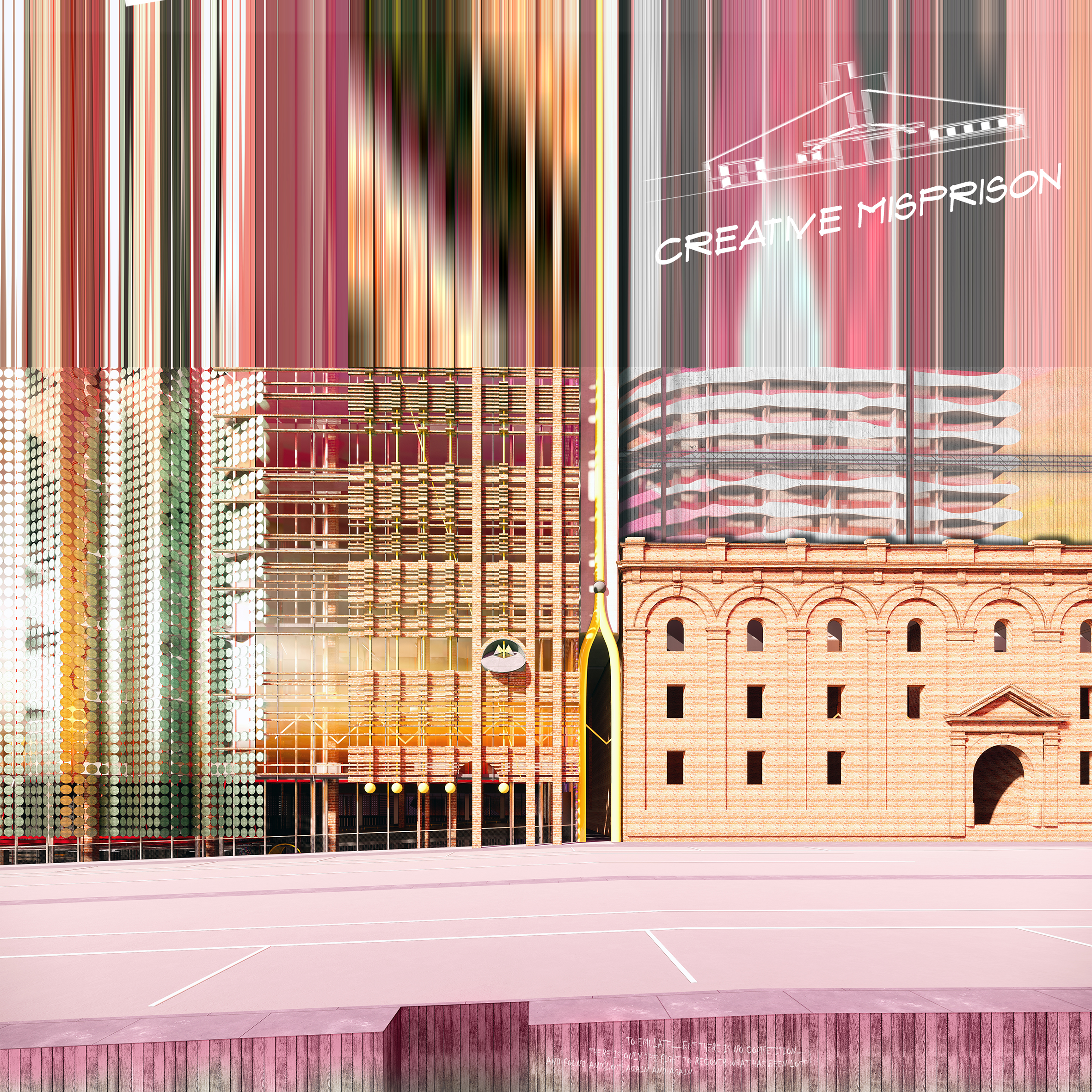

TEN / Creative Misprision

System: The creative misreading or deliberate misinterpretation of a precursor system as a method of forward movement.

Example: Here, Howard Raggatt deliberately misinterprets Robert Venturi’s Vanna Venturi House resulting in a building which both contains that from which it came, and one that perpetually attempts to run away from its prior self.

Translation: An example of creative misprision in the original Design Hub is the intentional misuse of webforge to subvert traditional understandings of wall cladding in an architecture school. Moving one step further, my project seeks to reinstate the traditional understanding of webforge as transparent in the processional stair/ entry to create an ethereal curtain of the already ubiquitous building material. This sees the preservation of the original material, while reframing the architecture adjacent as ‘behind the curtain’ during entry. The experience of entry thereby becoming entirely the consequence of one of the building's characteristic materials.

“How is it that clouds still hang on you?” - King Claudius

ELEVEN / Maintained in Drawing

System: During the creation of a new architecture, an older understanding or concept is maintained through an archived document, usually a drawn plan or section. Usually, the concept or understanding is symbolic, and revels in a kind of liberative abstraction.

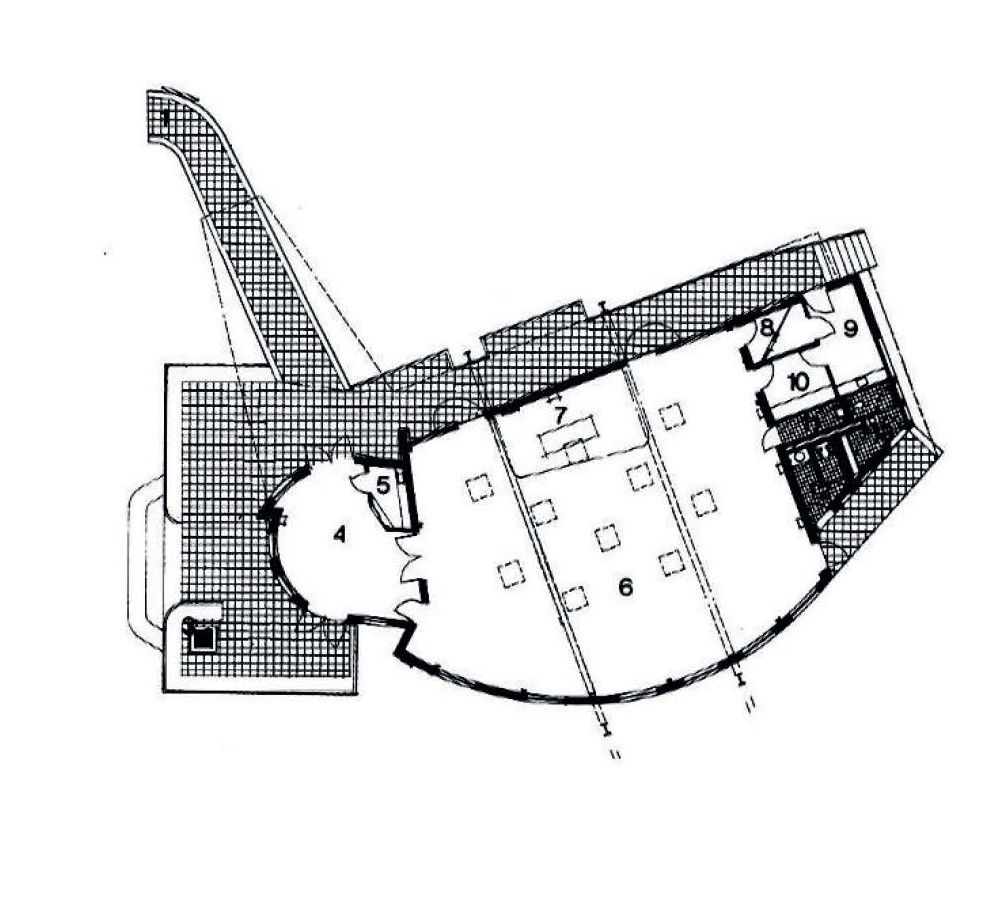

Example: In the plan of Edmond and Corrigan’s ‘Chapel of St Joseph’, is a hidden figure of Christ as a baby. This informs a new, contemporary experience of a church entry vestibule and knave whilst maintaining the tradition of the church plan as symbolic of Christ’s life.

However, where traditionally a church is formed from the image of Christ’s crucifixion, Edmond and Corrigan celebrate the beginning of Christ’s life and the immaculate conception.

Translation: Although never experienced literally, the ‘mushroom cloud’ exists in section as a representation of Hamlet’s necessary annihilation. While it is hidden from those who may reject the notion of a mushroom cloud in a school, it can be exposed to those who seek out the abstracted view.

This also brings into question any methods of representation that an architect may utilise in order to preserve their concept - even if it could be considered subversive or contradictory to the ideas of their client. This speaks to the subversive power of our abstracted language.

“Prayer at the calamitous annunciation.” - T.S. Eliot

TWELVE / Preserved as Metaphor

System: This system describes the use of a symbolic architectural gesture as representative preservation.

Example: In his sculpture, ‘Project for door’, Gaetano Pesce uses another entry/exit to preserve a dilapidated existing entry/exit.

Translation: The skull atop all else is something of a telos or capstone for the project. It is both the secular prayer and also the answer that never arrives. It perhaps represents the end of my own preservation at this institution as equally as it is Yorick’s skull pressed against the angsty Hamlet below. Herein lies the power of metaphor, always providing ‘almost answers’ through a kind of awesome multivalence. In using this, one should beware eisegetical trapdoors.

The hope and the love and the faith are all in the waiting.” T.S. Eliot

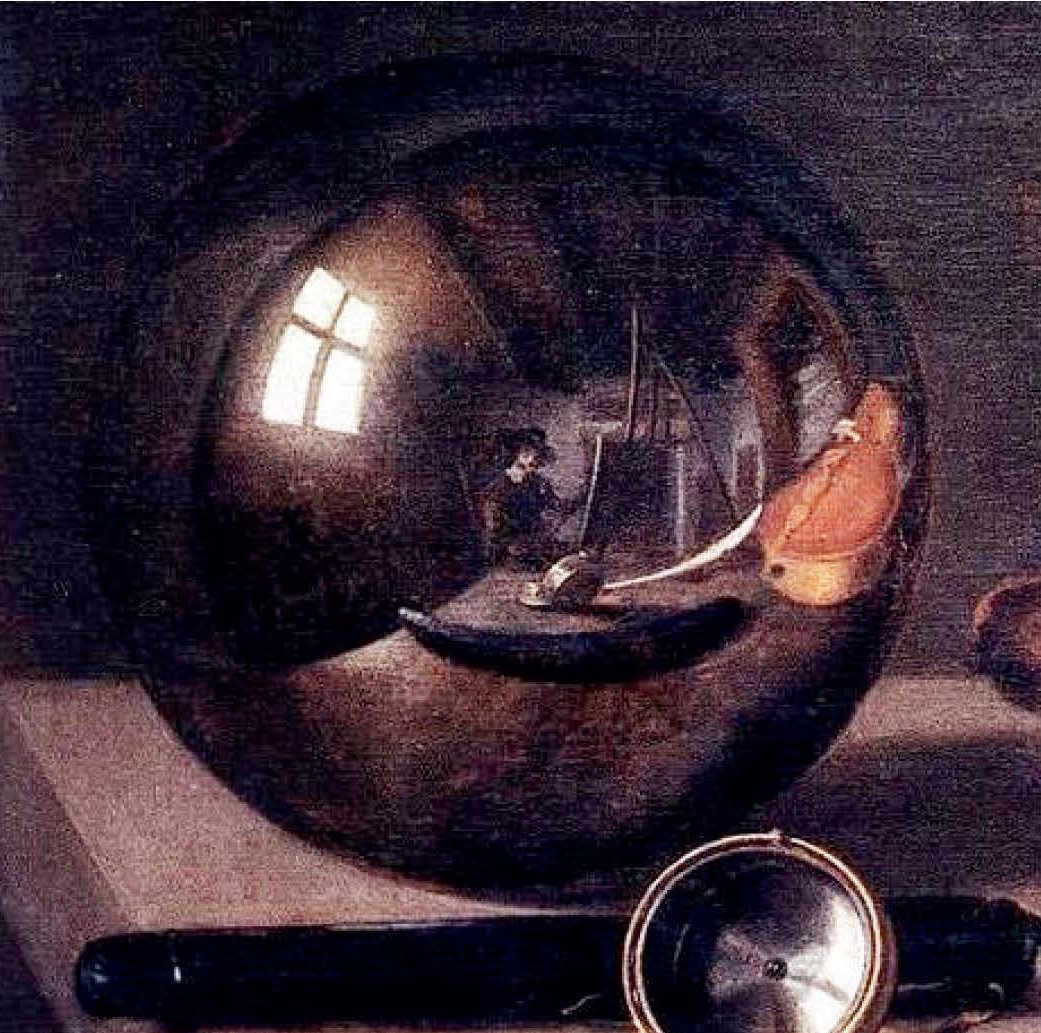

THIRTEEN / Self Preservation

System: The creator makes an effort to preserve themselves within the work so that they may exist beyond their own mortal ability.

Example: In 1628, Pieter Claesz paints himself into ‘Vanitas with Violin and a Glass Ball’, to preserve himself in time, and consequently living forever in the painting.

Translation: Self-preservation forms a complicated part of this undertaking. There are no tectonic systems that write me into the project. However, this major project as a whole has been undertaken as an opportunity to interrogate my own understanding of the framework in which I operate.

The project is acutely aware, as Shakespeare is through Hamlet, that it must operate as myself within the Globe Theatre (RMIT) in the world (the ‘globe’ as the world). Any preservative measure thereby becomes as real and lasting as the project.

“Remember me.” - King Hamlet

POSTSCRIPT / Pressed against the world, the institution, the profession and me.

This project can be called somewhat reactionary. It responds and stands in opposition to evident shifts towards quantifiable systems of value in the practice and learning of architecture. Primarily, its argument being that these systems of value, be they economic, ecological or the like, already maintain developed languages for their expression.

Architecture, however, as understood through the applied Shakespearean lens, contains a capacity to reach beyond, and into the unknown, unquantifiable realms of human intellectual thought, thereby deserving a place at the ‘table of lofty contemplations.’

In short, we have built-in to our profession complex abstract and formal languages which can either submit and reinforce other systems of knowledge, or rather, could be used to explore our own capacity to interrogate and influence ourselves and the world around us (i.e. producing Hamlet).

And herein lies that difficulty that is ‘the rub’.

While it is undeniable that each built project is often at the mercy of many other more quantifiable systems of thinking, this does not and should not mean submission – rather, it should mean a fight for our capacity to partake in a kind of wondrous thought that endeavours to accept our role as Milton may have written it and reaches to realise the ‘Poem: Unlimited’.

Surely Shakespeare, Bloom, Hejduk, Hamlet and the Globe myth qualify us for as much.

Towards the end of this thesis, Harold Bloom sadly passed. The feeling was, to say the least, strange. I hope this project which founded itself in his pages and leapt into architectural thought can be my small act of preservation in memory of Professor Bloom.

︎︎︎

Note from the editor:

Note from the editor:

There is a complex engagement developed between Koutoulas’ architectural agenda and his source text, Harold Bloom’s Hamlet: Poem Unlimited in a literary and experiential sense. Drawing on Bloom’s analysis of Shakespeare’s most existential tragedy, Koutoulas seizes on anecdotal architectural accounts contained within the book, along with the rapidly devolving maelstrom of the play itself to cast the architectural project adrift in a field of indecision and irrationality. There is no necessity for this project to come down on one side or the other – Hamlet provides no simple answers to his own questions.

In his despairing existential doubt, the prince of Denmark states directly to the audience “To be or not to be, that is the question”. The question is not posed to the audience except in an abstract sense, for the whole monologue he maintains his critical distance from the question of existence, getting caught up in his own examinations rapturously exclaiming that “end[ing] the heartache…is a consummation devoutly to be wished”.

For Hamlet in this moment comes the realisation, the titular “rub”, that “in sleep what dreams may come” – he claims “the dread of something after death” as a spatial construct, “the undiscovered country” that “puzzles the will”. Through an architectural reading of this spatial dread, and the indeterminacy of existential questioning filtering through his own urban and tectonic attitude, Koutoulas maintains a firm grip on rigorously uncertain ground.

The architecture of The Rub is one of a positive feedback loop caught in time, developing layer upon layer of architectural complexity as a consequence of the redeployment of the transformative act of the Globe Theatre’s dislocation across the river Thames. As Leon describes “It tries to answer every question with satisfactory precision but answers nothing quite well enough.” – and in that constant shifting of expectations, it attains a kind of hazy resolution.

The constant traversing between preservation and progress makes the building almost anthropomorphic. It does not contain the precision of a building as a singular artefact, but rather the messy and chaotic nature of human experience.

This project is constantly in flux, defined only by its adjacencies.

It makes us wonder whether this major project is somewhat autobiographical; within Shakespeare, his character of Hamlet, Sean Godsell, Building 100, and Leon himself.

“Aye, there’s the rub, for in that sleep of death…what dreams may come?”

The architecture of The Rub is one of a positive feedback loop caught in time, developing layer upon layer of architectural complexity as a consequence of the redeployment of the transformative act of the Globe Theatre’s dislocation across the river Thames. As Leon describes “It tries to answer every question with satisfactory precision but answers nothing quite well enough.” – and in that constant shifting of expectations, it attains a kind of hazy resolution.

The constant traversing between preservation and progress makes the building almost anthropomorphic. It does not contain the precision of a building as a singular artefact, but rather the messy and chaotic nature of human experience.

This project is constantly in flux, defined only by its adjacencies.

It makes us wonder whether this major project is somewhat autobiographical; within Shakespeare, his character of Hamlet, Sean Godsell, Building 100, and Leon himself.

“Aye, there’s the rub, for in that sleep of death…what dreams may come?”